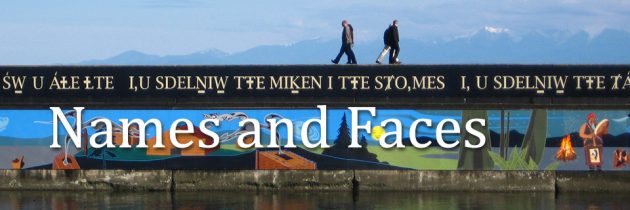

Names and Faces

by Darren Spyksma, SCSBC Director of Learning ◊

Five years ago, I received a paper bag full of notebooks, report cards, written essays and reports from my time in grade school. Digging through the pile, I came upon a green folder with the title Nootka. I was instantly brought back to those school days when I worked on this assignment. I recalled the tears shed over writing and rewriting pages of my report in cursive (I was not allowed to use whiteout). I remember the various iterations of the orca that took up most of the cover page. I was proud of this project. I still felt pride in this project – until I opened it and read it again.

The traditional elementary research report included paragraphs on housing, food, government and so on. In the eleven pages of single-spaced, handwritten paragraphs, three things struck me. First, I understood again the uselessness of the grade letter B when it is all you receive as feedback. Second, the entire report was written as if the Nootka were in the past. I had not been coached or taught that the research I was doing could have been living research. Last, and potentially just as damaging, there was no reference to the impact of residential schools on the Nootka people. For reasons beyond explanation in this story, residential schools and their impact on the indigenous population in BC were not part of my Social Studies. I am pleased that the educational climate in BC has changed since that time in our history.

As Christian educators, we have a call1 placed on our lives which is both a privilege and obligation. We are called to support reconciliation and regeneration of our local indigenous communities. With deep respect, I share my story of growth in acknowledgement, affirmation, appreciation, and fledgling understanding of various indigenous communities in BC in the hope that my story can help others on this essential journey of reconciliation and regeneration.2

My story is one of movement from ignorance to appreciation and commitment., moving from a place where it was easy to disregard the history of a nebulous group called Aboriginal to a place of friendship with people called Carey, Mary, Brian and Roy Henry. A journey combining openness, opportunities, and courageous leadership encouraged us as staff through the words of Rod Wilson, who suggested that before we talk about and judge others, we first need to be able to “know faces and names,” suggesting that our work needs to be rooted in relationship. This is especially important for school communities who want to know, appreciate and invite their indigenous neighbours into their community. My experiences have taught me I am not a completely fulfilled child of God if I am not in relationship with my indigenous neighbours who continue to teach me about responsible stewarding of creation, relationships, and time.

My learning has been exponential in the past two years. This summer, I stood beside a Haida Watchman at the foot of a totem pole in an abandoned Haida village as he shared the details of the Haida Nation losing close to 90% of its population after contact and colonization. As a nation based on an oral tradition, this meant losing 90% of their history. I have met young proud Haida carvers and university students whose families have survived residential schools who are planning to protect aspects of their heritage through cultural tourism.

I worked with leaders in multiple indigenous communities, who can name only a handful of homes that have not been directly affected by the impact of residential schools. Even now, you can walk the streets of communities at night and hear the unrest that is the consequence of poverty and the loss of a generation of leaders.

I sat overlooking the banks of the Kispiox River with Roy Henry Vickers discussing the reality that the church was welcomed into the local indigenous communities because “their stories were similar.” He told me that the story of salvation from the Creator is carved in stone in northern BC long before contact with European settlers. The culmination of this visit was being the encouragement to share the stories I am living and learning. “That when a story teller shares a story, it is a gift given to be shared with others.”

I enjoyed my first Educators and Elders Roundtable3 where I was reminded again that my ways are western ways. My education that day included a delightful lady patting me gently on my arm, saying, “After you ask a question, our people go to the right around the circle. You always go to the left.” Later on, after some farther reaching questions from me, I learned it would be inappropriate for me to speak for those people; I am not one of them. I can only speak for my people. Once again I was reminded, this is about names, faces and relationships.

Education has an important role in supporting reconciliation. The Ministry of Education believes this so deeply that understanding and reconciliation are part of the mandatory provincial curriculum. As I continue to build relationships with indigenous leaders in various communities I know that each indigenous nation in BC is unique. To lump all indigenous people into one group is like lumping all immigrants and refugees into one group. This sort of generalization makes for efficiency in reporting but is useless if the goal is meaningful, mutually beneficial relationships. For true reconciliation to take place, individual school communities need to invest in their local indigenous communities with a willingness to listen and learn. Our indigenous communities have so much to offer. Investment in building relationships with our indigenous neighbours is not an obligation or an act of pity, it is an opportunity to be more fully human within the diversity of God’s creation.

The risk for schools as they work to comply with government expectations is to make indigenous understanding about compliance. In this situation, schools must seek to know before being known. A mutually beneficial relationship between two communities begins with a mutually beneficial relationship between two people. Once we establish the need and benefit of partnering, schools need to Acknowledge the role of Christian institutions in the destruction of indigenous culture and communities. From acknowledgement comes the need to Act. Staff need to act on their passion for deeper relationship with local indigenous neighbours. As relationships develop, schools need to Invite the indigenous community into meaningful, ongoing participation in the school. As the community grows in understanding, they will also grow in Appreciation. This appreciation further Affirms this direction for the local school.

Life has a way of twisting and turning in directions that are full of surprises. How assuring that we live in confidence that our Creator God holds us, supports us, and guides us. So it has been with me and my deep, growing appreciation for my indigenous neighbours in a place I call home on the unceded territory of the Sto:lo Nation. My path in education allows me the privilege of naming old and new friends in indigenous communities around the province, rich cultural communities that proudly carry the names Nisga’a, Haida, Hul’q’umi’num, Anspayaxw, Ts’msyem, Gitxsan, and Sylix. May my story encourage others in their journey of reconciliation and regeneration of all indigenous communities.

References

- Isaiah 1:17, Amos 5:24, Micah 6:8, Matt. 23:23, Luke 11:42

- Vickers, R. (2017). Address to Christian Principals Association of British Columbia Conference.

- Thank you to Jonathan Boone for the suggestion and Jeremy Tinsley for helping to make it happen.

Photo Credit: Brian Burger, CC. Na’Tsa’Maht Unity Wall mural on the breakwater at Ogden Point in Victoria, BC. www.theunitywall.ca.